SOCIALS

A few days of radioactive seclusion

In: Health

Tags: #thyroid-cancer #cancer #health #family #writing

Part 1: My thyroid got cancer Part 2: My thyroid got cancer: one year later Part 3: The thing that won't go away Part 4: Here I go again Part 5: And now, a bit of certainty

The pill is smaller than you’d think. It’s oblong with red and white caps. It comes in a cylindrical container, tapered at the top like a perfume bottle.

“We call it the rabbit,” the radiologist joked to me, stepping back as the nurse opened it and took out the pill. She placed it carefully in a small plastic pill cup and handed me a larger cup filled with water. They watched me as I swallowed the pill and drank the water. Then she asked me to take a couple of steps back and held a geiger counter towards me, her arm straight and stiff. She nodded with approval.

I was officially radioactive.

The days leading up to my "therapy dose" of iodine 131, a radioactive isotope with an eight-day half-life designed to kill the thyroid cancer remaining in my lymph nodes, were a blitz of scans, meetings, and blood labs. They warned me it would be like this.

It started on a Monday. I took a shot of thyrogen, a synthetic hormone that mimics what my pituitary gland produces when it doesn’t see enough thyroid hormone. It’s meant to send my thyroid cells into overdrive, looking for the iodine required to produce the thyroid hormone. To make them even more thirsty, I spent the preceding two weeks on an iodine fast. Essentially, this meant no seafood, no dairy, and no sea salt (but really, to be safe, no processed food with any salt — because it might be iodized — which essentially meant no processed food at all.)

The waiting room.

The waiting room.

On Tuesday I took a “test dose” of iodine 131, just enough to show up on scans but not enough to be dangerous. I went immediately from the nuclear medicine department to the LabCorp office for another quick blood draw. Then I was home for the rest of the day, catching up on work and preparing to disappear for a few days after the therapy dose made me officially, dangerously radioactive.

On Wednesday I got up early, before my kids were awake, and skirted back to the hospital to get scanned. They wanted to confirm that the iodine was taken up by the thyroid cancer cells on the lymph node they had already biopsied. This would confirm that everything was working as expected: the thyrogen activated the thyroid cancer cells and my low-iodine diet successfully starved them. As soon as the radioactive iodine entered my blood stream, it should have been picked up by those cells.

The scan took a long time. The room was cold, and I must have looked pretty odd walking in there with my solid green swimming trunks, t-shirt, and sandals. I went there already dressed for my mountain seclusion. I should have worn socks, though; my feet got cold during the scan and I had to stay completely still. With my arms strapped to my side, a large flat white plate, maybe two feet square, lowered within an inch of my nose. It stayed there and then ever so slowly, a centimeter at a time, inched toward my torso. To force myself to ignore the urge to itch my nose, my cheek, my ear (of course as soon as my arms are strapped down, everything itches), I thought about the novel I wanted to write. I thought about what meats I wanted to grill at Pinecrest. I thought about anything other than being flat on my back with a big square plate slowly traversing my body.

The scan took 45 minutes and I was escorted to another machine that did 3D scans. For another 22 minutes I sat with my face sandwiched between two more square white plates. This time they rotated around my head. I closed my eyes again and waited.

Finally, I was done, and the radiologist man with the short brown mustache sat in front of me with a look of approval.

"We saw two focii in your neck but we didn't see any others, which is good." He turned the computer screen toward me and I saw the outline of my neck with two white clouds right in the middle of it. This doctor warned me before the micro dose that it was possible they'd find thyroid cancer cells where they don't want to see them: on my lungs, liver, or stomach. He said he's seen it spread like this before, and since two years had gone by since my surgery, it was possible that my mild cancer could have turned into an aggressive one.

This was not something fun to think about. Great, more scanxiety, I thought. As I'd done during the many ultrasounds and MRIs I'd taken in the past, I listened and watched for clues. Even while my eyes were closed, even while I tried to think about something else, I'd pick up on the technician's taps and clicks, the way her weight would shift, whether her breathing would change. I thought these might be tells as to whether she was seeing cloudy blobs where they weren't supposed to be.

I could tell as soon as the radiologist walked in that there were no surprises. I was okay. He came in chipper, perhaps as relieved as I was that we could proceed as planned. If they found it elsewhere, there would probably be more tests and scans, my treatment might need to be delayed, or they would need to opt for surgery to take out a bunch of lymph nodes.

Instead of just one lymph node with cancer, I had two, and for the second time this doctor told me this was not a huge deal. "If I can see it, I can kill it," he repeated. I liked this guy.

He told me come back a few hours later for the real deal, after which I would need to follow some precise rules to keep my fellow humans safe while in seclusion up at my happy place.

It was still pretty early when I headed back home. My wife had already taken my girls to school. I'd already done the grocery shopping I needed for five days at the cabin. So, I went home and waited.

The pill, the very radioactive one, didn't taste like anything. I read on Reddit that some people experienced a metallic taste. I didn't. I had no nausea, no headaches, no symptoms at all. I walked back to my car, conscious of the fact that for the next couple of days I would not be able to throw anything away that I put my mouth on.

"The dumps have dirty bomb detectors," my radiologist explained. "They'll detect radioactivity on that beer bottle or Coke can and trace it back to me and you. Then we'll both be in trouble."

Blue was in my car, patiently waiting for me. Since I was not supposed to spend more than 2 hours in close quarters with anybody, even pets, I drove him about 40 minutes to Dublin, where I met my dad. Blue would drive up to the mountains with him and I would go the rest of the way alone with my radioactive isotopes.

I stopped in Oakdale because I was hungry. There was a taco truck outside a fruit stand, so I quickly confirmed with the cook that they don't use sea salt and ordered a carnitas burrito, no sour cream, no cheese. I had to stay on my low-iodine diet for two more days. That burrito was awesome. Since I ate it all and was careful not to put my mouth anywhere on the foil, I threw the packaging away.

Such a weird thing to need to be careful of, I thought.

Up at the lake I was able to carry my bags and groceries to our boat in the marina in one trip. The engine started and I sped to the north shore, content that I didn't put anyone in harms way and kept any stray bits of radioactive iodine safely inside my beige Toyota Camry.

My dad arrived about an hour later. I'd already unpacked all of my groceries, began to thaw the frozen meat, and popped open a beer. It was hot that day, and I smiled as I recalled the advice my radiologist gave: "Drink as much as you can," he said. "Beer, wine, water, whatever. I want you to drink so much you have to wake up in the middle of the night to urinate."

Cheers to that, I thought as I popped the cap off my Lagunitas IPA.

My dad texted when he arrived. I pulled our little boat up to the loading dock on the south shore of the lake, grabbed my dad's bags and groceries, helped him into the boat and turned back around to the north shore.

It was about four in the afternoon on a Wednesday. My radioactive seclusion had officially begun.

The following days were wonderful. I'd been up to Pinecrest several times already this summer, but being up for five days with just my dad was a treat. It was the unexpected benefit of having radioactive iodine therapy. Seclusion is not something I get much of anymore as a husband and parent, and most certainly not for five days in a row.

The days were split in two. We'd exercise in the morning with a long hike, make lunch when we returned to the cabin a few hours later, and then I'd get the next 4 to 5 hours to focus on writing a novel, something I'd always wanted to do. I decided to take this opportunity to give it a running start. When I was done writing around 5 in the afternoon, I'd start the fire and get the coals ready for grilling dinner.

Thursday we woke up to oatmeal and coffee and decided to hike up to Herring Creek, a beautiful waterway through dense forest that merges into the Stanislaus just south of Pinecrest lake.

It had been years since I hiked this trail and decades since my dad and I had hiked this trail just the two of us. The huge fallen ponderosa log leading up to the first big climb had nearly decomposed. When I was younger, 20 or so years ago, I could walk along that log. The bark was still on it back then. Now the whole thing was practically dust.

At the top of this first incline there used to stand an old ghost of a cedar. Its leaves and branches had long since fallen away, and it leaned nearly twenty degrees off center, toward the lake and away from the trail. When I was much younger my dad and I would throw rocks at that tree, trying to see if we coould tip it over. As I got older and stopped hiking that trail, my dad would send me updates. Finally, this past spring when he hiked up there with my aunt, he told me it had fallen and sent this picture.

Where the old leaning tree used to lean

Where the old leaning tree used to lean

It was bittersweet to see it myself, halfway up to Herring Creek. It was an odd reminder of my own mortality: I was at Pinecrest to recover from cancer treatment, keenly aware of the aging world all around me.

At the top of the ridge, the trail flattens out into a pine forest with several small ponds filled with reeds and lily pads as it winds its way to the creek. A long the trail there's a fork that angles back up a steeper ridge. It's known as the Lookout Trail, and connects at the very top to a network of trails that traverse the entire Sierra Nevada mountains.

I was feeling good and didn't want to turn around just yet.

"Are you up for going to the Outlook?" I asked my dad. The outlook is a spot along the Lookout Trail that leads to a large granite shoulder overlooking the lake and the south fork of the Stanislaus River that feeds it.

He agreed and we took that turn back up the mountain.

We talked for most of the hike up the hill, which is a bit unusual for us because neither of us particularly enjoy starting conversations, so our phone calls are always short. My dad is a quiet, thoughtful person, happy to go along with whatever the situation calls for. He'll talk if I want to talk and will stay quiet if I don't. Since I knew this time together was a rare opportunity, I kept the conversation going, asking him about his relationship with my grandparents, with my aunt and uncle, and his childhood. We talked about work and politics and I lost track of our time on the trail. Before I knew it, we would be back at the cabin eating lunch.

Lunch is familiar ground for us. For the last ten years or so, our visiting routine was for him to meet me for lunch every month or so. He travels and I pay, a trade I'm happy to make. When I worked in San Francisco, my dad would catch the BART in Fremont, take it into the city, and meet me at the Scripted office. I remember him coming for lunch at each of the offices we had back then. We'd go to a restaurant and catch up about the normal things you catch up on: work, health, relationships. Since I don't talk to my half-sister very often, I'd hear about her through my dad.

After my wife and I moved to the suburbs and I was able to work from home, he would drive to our house and since my kids don't have pre-school on Fridays, he'd get to visit with them too. I'd usually have take-out delivered or order sandwiches and we'd inevitably wind up at the creek where he loves to throw rocks for Blue as much as I do. It's funny how little things like that, the satisfaction of throwing rocks in a creek, demonstrate to me that I like this guy and yes, he's my dad.

We don't talk on the phone or email much. He sends me articles from the San Jose Mercury News that I'll always read and usually comment on. And then roughly every four weeks I'll get a text from him to set up a lunch. I really enjoy this routine and the rest of my family appreciates it too. I thought about all of this on the days my dad and I shared up there.

On Friday we hiked up to Cleo's bath, a section of the Stanislaus where it runs almost entirely over granite rock, emptying into deep pools with small and large waterfalls. It had also been years since I hiked it, and I recall that last hike was depressing. It was during the nasty drought California faced between 2011-2016. I hiked with a couple of friends and discovered the baths were dry. There was hardly a trickle and the water that was there was stagnant.

I figured this year, with the long winter and late thaw, would be good. I was not disappointed.

It was refreshing to see Cleo's bath replenished and beautiful, the way I remembered it from summers past when we'd hike up several times and go further up the canyon into what my grandpa called the first and second forests. My dad and I didn't talk as much on this hike. I was content to soak it all in. The weather was perfect and the water felt great, crisp and cool, snow melt warmed by the summer sun. I jumped into the small waterfall pool and my dad, not having a swim suit, stripped down to his underwear and joined me. It was something I would also do if the situation called for it. However, this trip, the only shorts I packed were swimming trunks. I was prepared to be in the water several times a day.

On Saturday, instead of hiking, we swam from our boat dock to the swimming cove, about 15 minutes each way. Since this was a lighter workout, we supplemented it with a Peloton core workout routine I had downloaded to my phone. My dad went along for all of it, keeping up with me on both the swim and the floor exercises. For a guy pushing 70, it was remarkable. I hope I can do the same when I'm his age.

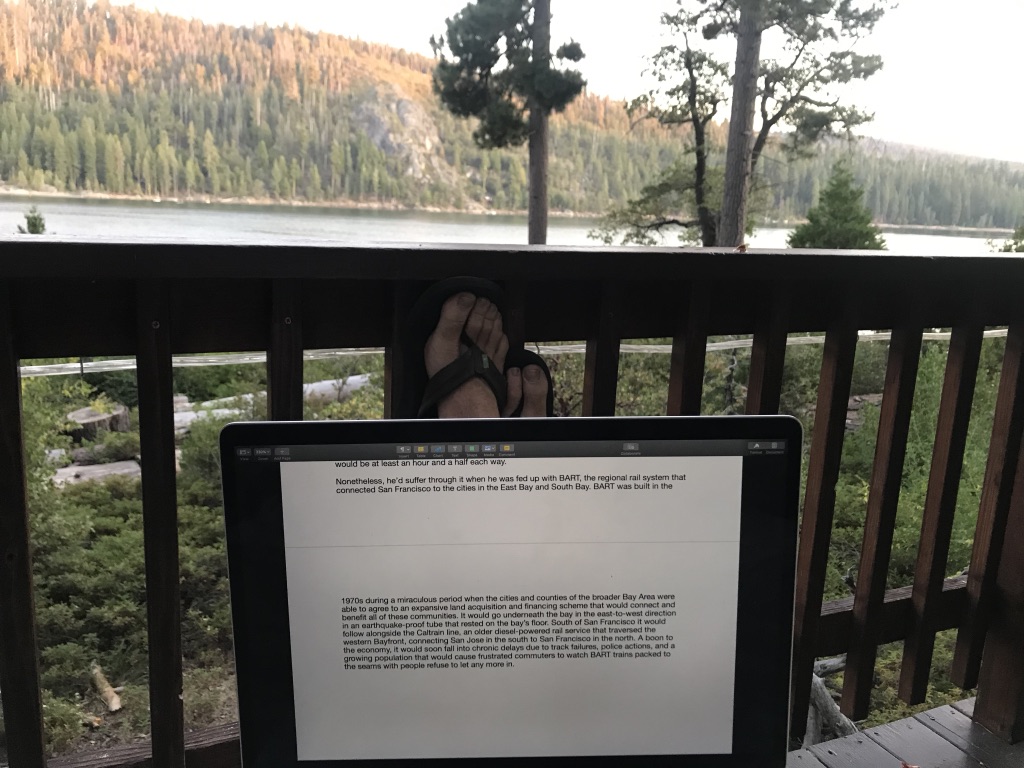

I was okay with the truncated morning routine, though. I had writing to do, and I wanted to break 20,000 words on the trip. As it turned out, I got up to 28,000 words before I drove back home. In the weeks since I've had to focus my writing in other areas, but I'm now over 32,000 words and figure I'm a bit less than halfway through the novel. It's a labor, but calling it a labor of love would be an understatement. I think about it all the time and can't wait to dive back in.

Is there anything better than writing a novel lakeside at sunset?

Is there anything better than writing a novel lakeside at sunset?

Our evening grilling was on point. I don't have a picture of every meal, but I did snap a pic of the wood fire BBQ'd salmon since it was perfect. I got the coals just right and this filet flipped over without sticking anywhere.

A perfectly grilled Atlantic salmon

A perfectly grilled Atlantic salmon

This particular dinner was symbolic because it meant my radioactive iodine treatment was over. I could go back to seafood and dairy, which meant I could eat salmon, cheese, and chocolate, the three foods I missed most in the preceding two-and-a-half weeks. I did not have to skimp on alcohol, at least, and got to enjoy this bottle of whiskey that one of my doctor neighbors generously gave me before I left.

A perfect place to sip Basil Hayden's

A perfect place to sip Basil Hayden's

The long weekend at Pinecrest was as uneventful as it was eventful. Although I was radioactive, I had no symptoms, and the treatment and scans had no complications. This was the best that I could have hoped for. On the other hand, the five days I spent with my dad were some of the most memorable we've had together. It had been at least twenty years since I spent time like this alone with my dad and I'm very grateful that we had this opportunity and took it. I'm glad my wife encouraged me to do it and that my dad was willing to disrupt his routine for a few days, risk some exposure to his radioactive son, and take advantage of this special time together.

More from Health

- Why I run - Sun 02 January 2022

- And now, a bit of certainty - Sat 27 April 2019

- Here I go again - Fri 22 March 2019