SOCIALS

The importance of electrification

In: Technology

Tags: #sustainability #environment #climate-tech #technology

This is a long post. And to make my long post even longer, I begin with a preamble.

I visited my mom recently and spent a lot of time in her house. She entertained my kids and my wife talked for a while with my stepdad. I stumbled upon a pamphlet I recognized while rummaging through magazines on the side table by her couch. It was for an awards banquet at UC Berkeley in 2005. I was a recipient of the UC Berkeley Foundation Award, a special recognition for anyone doing interesting stuff with alumni. I had organized an alumni association for the College of Natural Resources, and that got the attention of the award committee.

I remember that night. I invited my parents, my grandfather, and Lisa Bauer, my mentor from the Campus Recycling and Refuse Services office where I worked as a student. I was really happy and tickled to continue receiving awards from Cal. Plus, I knew it would look good on my graduate school application.

Back at my mom's house, I read through my bio for the Young Bear Award and smiled. I handed to my wife and she read it. "You sure were into environmental stuff," she said.

I was indeed. Two hundred words of every conceivable environmental activity were packed into that description. It sounded like I never took a regular class. I did take classes, but I took them because I had to. And since I was an environmental sciences major, I took them because they were interesting. But I had a sense of urgency then. Global warming was coming and I needed my peers to become good environmental stewards, even if it just meant taking shorter showers and separating trash from recyclables.

In time, that passion faded. Al Gore produced An Inconvenient Truth, Leonard DiCaprio rode a Prius to the Oscars, and all of a sudden the whole world was talking about global warming. I figured the job was done. The former Vice President beat me to it. I quit the environmental organizing job I took right after college and looked to the private sector. I moved to LA and joined Navigant Consulting. I stopped thinking about environmental activism.

Fast-forward 15 years and boy... Could I have been more wrong? Al Gore didn't save us. Neither did Leo. And all I did in the meantime was get a couple of graduate degrees and start some B2B web companies. If I'd stuck with environmental work, I know what I would do right now.

I would focus on building electrification. Maybe it's not too late.

Why should everyone electrify their home?

Humanity produces 51 billion tons of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions each year. We need to get that number to zero (or reasonably close) as quickly as possible.

Of that 51 billion, about 29% of GHGs come from buildings.

Of that 29%, more than 85% of the emissions come from on-site fossil-fuel combustion (natural gas -- the remainder is leaky refrigerants).

When you multiply 29% by 85% you get about 25%. This makes it easy to remember: we can knock out 25% of our GHG missions if our buildings get electrified and the electricity comes from non-carbon sources.

To do that, we need mass adoption of electric building technology, and to do that, we need both political willpower and community activism. Then we need to green the grid, but that's inevitable at this point and easier to do because there are far fewer power plants (~1,500) than homes (~14,000,000) in California (and I assume the ratio holds nationally). So we need to tackle the home problem ASAP.

Fortunately, the technology is already here. It's available and it works great. The problem essentially boils down to economics: how do we incentivize people to do the right thing, even if it costs a bit more?

What's an all-electronic home?

Here are the main electrical components of a fossil fuel-free home. In most homes today these appliances run on natural gas.

- Electric central heating and cooling- Electric water heater- Electric cooktop- Electric clothes dryer

Fortunately the non-gas appliance options all kick ass. I'll describe each of them and what we decided to do here with our own major remodel.

Heating air without burning gas

I admit that I didn't think about this one at all when my wife and I launched our remodel and expansion in early 2021. I didn't ask to switch out our gas appliances and our contractor didn't suggest to me that we do. It wasn't until I read the Bill Gates How to Avoid a Climate Disaster book that I realized I had an opportunity to be part of the solution. I decided that our remodel was gonna go green.

So, how do you efficiently heat air without burning fossil fuels? You purchase a magical device called heat pump.

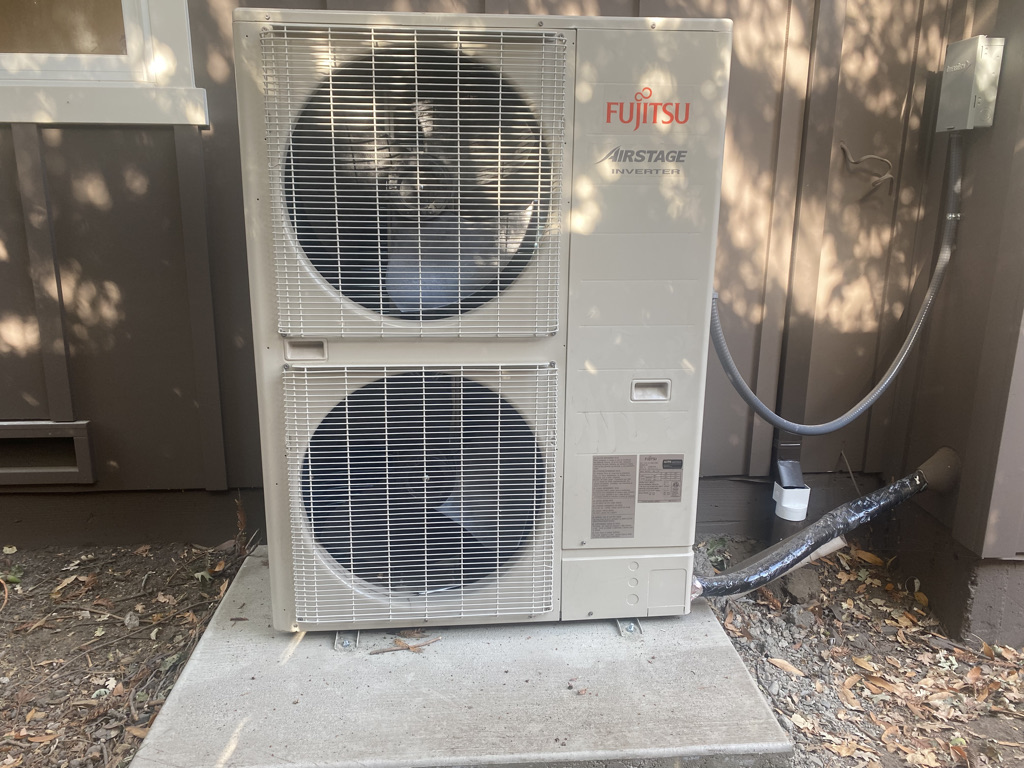

Our Fujitsu heat pump

Our Fujitsu heat pump

A heat pump is a refrigerator in reverse. It uses the thermodynamic properties of refrigerant to capture heat and transfer it somewhere else. It can heat your home when the outside temperature is very cold, even below freezing, by dropping the temperature of the refrigerant fluid far enough below the ambient temperature to create a heat differential. The energy from that difference in heat warms your house. It's magic.

When it's hot outside, the system runs in reverse, using the same principles as your refrigerator and freezer to cool you off. Heat from the inside of your house gets absorbed by the refrigerant and again using thermodynamic magic, that fluid gets cooled and produces cool air. The heat pump unit does both the heating and the cooling and can toggle back and forth (but can't do both simultaneously).

I asked my friend Wei-Tai Kwok about his decarbonization project and he referred me to a blog post about his electrification project about his project. I asked him how well the heat pump units heat and cool his home; he said they work great and they're really quiet. He had no regrets.

I wanted to learn more about this technology, and I found this:

In a study by the city and county of San Francisco of ways to reduce emissions 80 percent by 2050, researchers found widespread adoption of electric heat pumps to be the “single most important lever considered.” Heat pumps are currently the most efficient available technology for space heating in the commercial and residential sectors. Although heat pumps have high initial capital costs, high efficiency and minimal maintenance make air source heat pumps a positive financial investment over 20 years.

Center for Climate and Energy Solutions report by Jessica Leung

I asked my general contractor about switching out our furnace system and putting in a heat pump. We were still pouring foundations at the time, so it wasn't too late to make the change, but he was skeptical about the power draw.

We have a 120 amp system (standard in our area) so that's the limit on how much current we can consume at once. An electric furnace uses 60 to 80 amps. If we had that on and were cooking and our water heater was firing up too, we might hit capacity. He advised me against it. When I pressed him on heat pumps, he confessed to not knowing about their power needs. He promised to ask Bill, his HVAC guy.

Bill responded with good news the following day. It turned out the heat pump would use less than half the amps that a purely electric furnace would use. It was essentially the same electricity profile as the original system, so we were good.

My contractor relented. I could get the heat pumps!

I spoke more with Bill and I learned that he'd been pushing heat pumps on my contractor for a while. He was happy to get a large residential system installed. He said half of his jobs involve heat pumps now and they last a really long time with far less maintenance.

Furthermore, with a typical mini-split system we could have temperature-controlled zones throughout the house. My kids could adjust their own temperatures in their rooms and we could turn it off completely in the common rooms overnight. Our last system was a single zone, so in the winter we were heating an empty living room, hallways, and kitchen all night. I loved the idea of having all these zones so we only heat and cool small parts of our house at any given time. I told him let's do it.

I got the quote a week later and we needed to pay $20,000 extra for the system we talked about. I don't know how much of that was my desire for five zones or the complexity of wiring the system upstairs where there's no attic or crawl space, but I didn't protest. I wanted the better system that would use less energy and no fossil fuels. Since it was still early in our renovation process I could stomach the difference. It would have been much harder to do towards the end. We agreed to the extra cost.

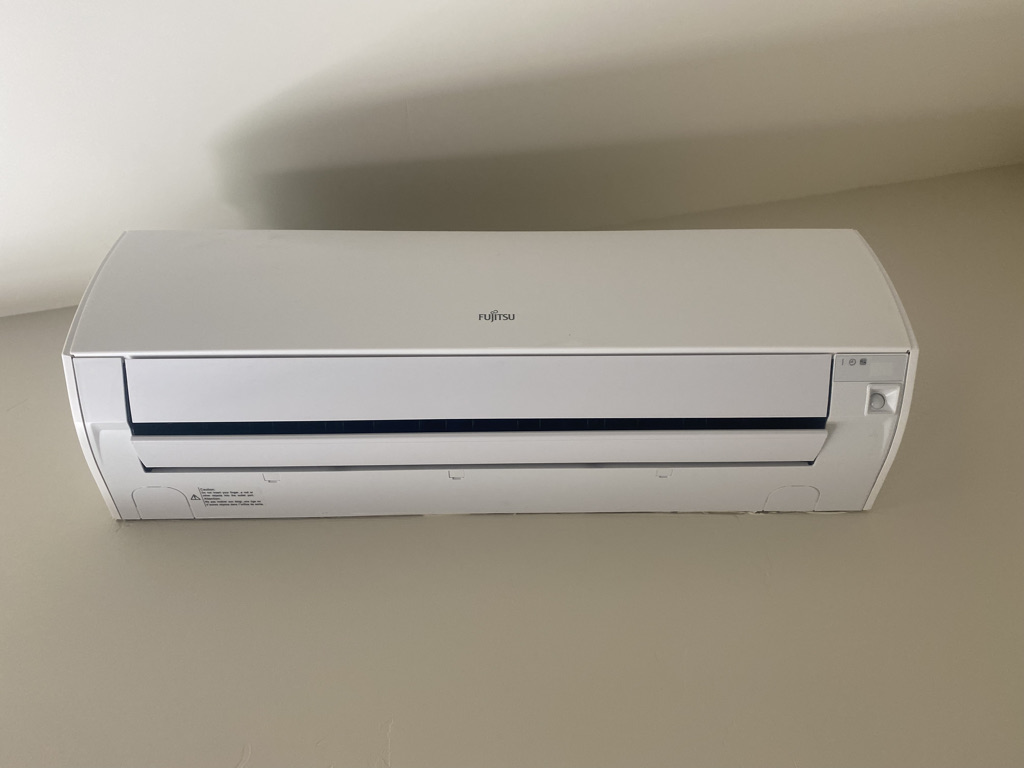

Lest you think that having a heat pump means putting one of these appendages up on the wall, rest assured that standard ducting works too. We have these upstairs because there's no attic or subfloor to run ducts. The only solution was the wall-mounted air handler which, by the way, is super quiet and works great. After a while you don't even see it. The rest of the vents look like this.

They're all very low-profile, normal vents and the ceiling air handler is especially slick. It's actually the equivalent of the boxy thing we have upstairs but we couldn't use it there because of the slant in the ceiling. The sleeker square air handler only works on flat ceilings.

So the way our heating and cooling system works is this:

- Kid Bedroom 1: Separate zone with square air handler in ceiling- Kid Bedroom 2: Separate zone with square air handler in ceiling- Guest Bedroom: Separate zone with boxy air handler in wall- TV room: Separate zone with boxy air handler in wall- Office and master bedroom and bathroom: Separate zone with floor vents (I forget why these needed to be combined, but they did. They share a wall in our new addition)- Open spaces: The kitchen, living room, entryway, and hallways share a zone

What this ultimately means is my kids can set their own room temperatures. They can go really cold or really hot at night. I don't care because it only impacts their room. At night we schedule our vent control system to "unoccupied" status so the heating and cooling is effectively shut off between 9pm and 6am. Then we can control our temp in the bedroom separately too.

We also put fans in every room to distribute the heating and cooling better and to take advantage of the the four to five months a year when we can enjoy mid-70s all day with the windows open. On those days, all we need is air circulation with the ceiling fans.

Our system does two great things: it uses no gas, and it heats and cools with precision. I'm really happy with it so far.

Heating water without burning gas

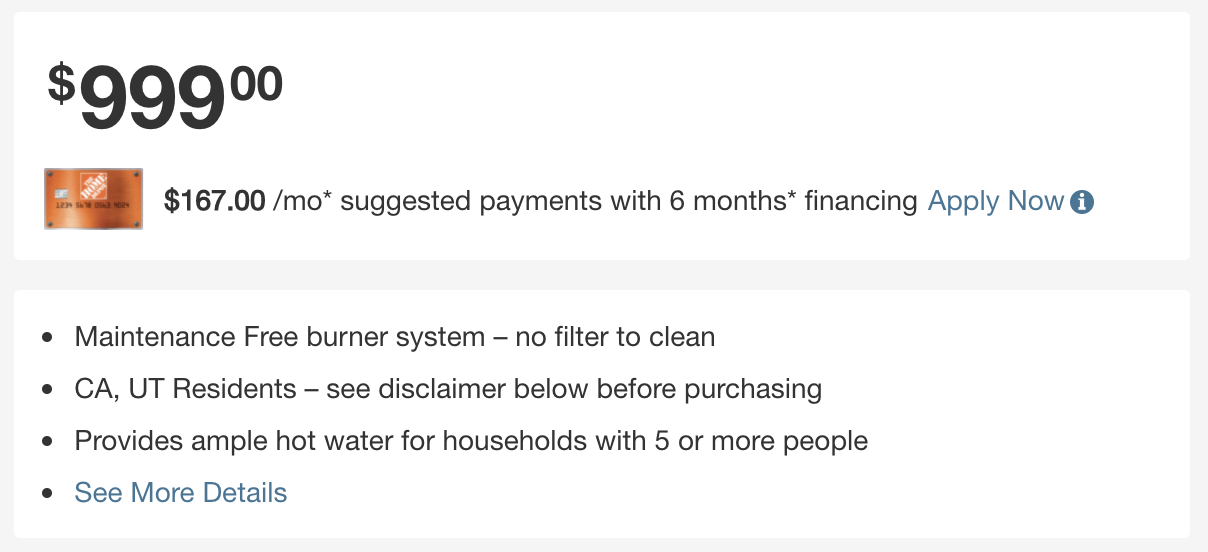

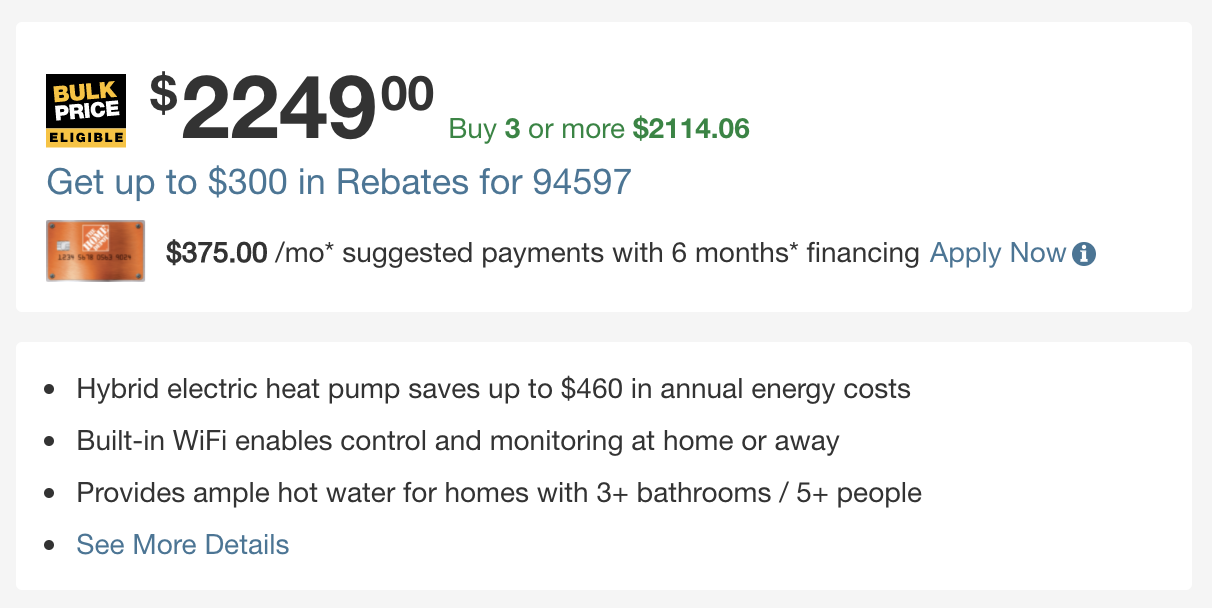

Heating water with a heat pump is a much easier proposition. We originally had a typical gas-fired 80-gallon water heater and after some quick research, I found a Rheem heat pump water heater that I liked at Home Depot and had it delivered.

Traditional gas

Traditional gas

Heat pump

Heat pump

The cost difference here was about $1,300. However, the energy efficiency saves several hundred dollars per year, paying this extra cost off in just 3-4 years. Since the lifespan is at least 10 years, this one's a no-brainer.

Because the water heater system only runs in one direction (transfer heat from the air to the water), the appliance constantly exhausts cool air. Therefore, in the summer months our water heater will cool down the garage. We didn't put any AC vents to the garage so this will be a really nice perk when it's 100 degrees outside. I don't like hot, stuffy garages.

As for performance, my friend Wei-Tai had no qualms. The water heater can keep up with his family just fine, and since my family doesn't take long showers, I suspect we'll be fine too -- the customer reviews are very positive.

Cooking without burning gas

I grew up using an electric stove, the kind with the metal coils that glowed orange as they heated. I had no problem with it. Boiling water took a while and the filaments were hard to clean, but it worked. My grandparents remodeled their kitchen and bought a different kind of electric stove. It had a glass top and glowed red from underneath. It was easier to clean but also took a while to boil water.

I got my first gas stove in college. I loved it. I liked seeing the flame, adjusting the burners, and feeling like I could control the heat better directly. Later, in grad school, I bought a small set of Cuisinart cookware to use on my gas stove in Cambridge. I use that same set of cookware today.

I couldn't imagine swapping out my gas range for an electric one. This was a bridge too far. But then I read about induction cooktops and I changed my mind. Yes, our entire kitchen was going to be electric, too.

Here's what we got:

Yes, we went Bosch all the way. That's because we didn't buy anything new! All of our appliance purchases came through Craigslist from people who changed their minds or somehow wound up with two appliances. Their misfortune was our gain -- especially since supply chain backups were going to cause major delays. It was nice to drive to someone's house and pick up a box with our appliance and take it home. (And if you're wondering -- all purchases turned out to be legit.)

Our ovens do not use heat pumps. These are regular old electric ovens with heating elements and fans that do the heating work. I think this is because heat pumps don't get that hot. Shower water is going to be 110 degrees or less. Anything above 140 will burn your skin within five seconds! A heat pump can get you there, but it can't reach the 350 or 500 degrees needed for a convection oven. This technology is back to basics, but that's fine. It's still electric, and we pay a premium to get our energy from renewable sources.

Our cooktop doesn't use heat pumps either. Instead, it uses magnets. But like a heat pump, it feels like magic. Behind the scenes, induction cooktops leverage the reaction of a ferrous material in the presence of a magnetic field to produce heat. Basically, iron molecules become really active and produce electronic friction which makes the pan heat up. The induction cooktop itself doesn't get hot -- it makes the pan get hot. This is what makes it super efficient.

When you use a gas stove, a ton of the heat from the flame escapes into the room. The sides of the pan get hot, the air around the pan gets hot... if you cook for long enough, the entire kitchen gets hot. This is a huge waste. You pay for all that heat. Electric stoves are wasteful in a different way. Electricity heats the resistance element, which (usually) heats some sort of glass or ceramic cooktop, which heats the pan, which then heats your food. Each layer of heat transfer creates energy loss. It's not as bad as gas, but not nearly as good as induction.

Remember: induction cooktops cause the pan to heat up, which directly heats the food. The air around the pan remains cool. The cooktop itself remains relatively cool -- it's the pan that heats the cooktop, not the other way around. So there still could be some residual heat, but it's not going to blister your hand.

Here's a really good video I found from a chef who has adopted induction cooking.

Watch this

Drying clothes without using gas

This one is aspirational. For now, we're sticking with our gas dryer because we recently bought it and I couldn't find a heat pump dryer that would match our washer dimensions. Call me vain, but I didn't want our washer and dryer to have different heights.

However, when the time comes, I will absolutely positively replace our gas dryer with -- you guessed it -- a heat pump dryer. I've seen this Samsung heat pump dryer and it looks amazing. No vents needed, just a standard outlet. The dry times take a bit longer, presumably because of the lower heat temperature, but that's fine by me. We're usually not in a rush when we run our dryer anyway.

This decision was a toss up between throwing or giving away a 2-year-old gas dryer to replace it with a new heat pump dryer, and that decision triggering the need (vain, again) to get a matching washer. That seemed a bit indulgent. We already have gas pipes in our home and we could build the exhaust vent into our laundry room. At this point I had already eaten the extra cost of our heat pump air system and I had buyer's fatigue. We didn't spring for the matching new washer / heat pump dryer combo. Instead, I'll look forward to adding this appliance to our gas-free family when our current ones wear out.

My closing argument for going gas-free

It's pretty simple, really. In the long-run, it costs less to build, it costs less to run, and it saves us from destroying civilization.

It costs less to build

- E3 report "E3 Residential Building Electrification in California", Apr. 2019, indicates that new all-electric residential construction will be less expensive as compared to homes with gas heating systems. - San Jose's new building electrification policy includes the following statement: "In most cases, all-electric buildings are less costly to build. The service and piping for natural gas is an expense that is often ignored when comparing the cost of gas and electric equipment. An all-electric building starts without that expense, so even when electric equipment might be more expensive in some cases than its natural gas counterparts, that cost is offset by the gas infrastructure savings."

It costs less to run

- Frontier Energy's Electrification Cost Story infographic showed that electric heating systems for single-family homes cost less to construct, and less to operate, as compared to gas heating systems.- Sacramento's new New Building Electrification FAQ includes the following statement: "Cost Savings: All-electric new buildings do not require the installation of gas infrastructure, reducing capital costs. New, and existing all-electric buildings can benefit from reduced operating costs. Studies have shown that cost savings for all electric construction can range, with potential savings upwards of tens of thousands of dollars, depending on the type of construction". - Wei-Tai Kwok's gas-free renovation resulted in lower overall cost. He recorded his energy costs and split between gas and electric before and after the conversion in a very detailed cost analysis.

It's less dangerous

Electricity is dangerous. It causes wildfires and burns down homes. But it's here to stay... we're not going to live without it ever again.

Natural gas is also dangerous, but it's optional. We can live -- and I'd argue we can thrive -- without it. As I was completing this blog post, I saw a news alert about a natural gas leak in Alameda, just 20 miles from me. Some residents were ordered to evacuate, others to shelter.

If that weren't enough, I've also seen my kids accidentally turn my gas stove on. They were building a fort in the kitched, pushed a chair into the stove, and managed to turn the knob in just the right position to light flame at full blast. I was in the other room and heard the clicking of the lighter before I noticed the flame. If I hadn't been home, if the blanket they used as the roof of the fort had caught fire... it would have been an absolute disaster. It would have also been bad if they turned the nob without lighting the flame, releasing gas into our kitchen. I can't think about it without getting chills.

But this is what families allow into their homes. Any kid can light a gas stove on accident, and they can certainly do it on purpose. There's no way for me to turn the stove off without unplugging it. If my kid turned on the induction cooktop, nothing would happen. It's so much better.

When my county put an all-electric new building ordinance up for a vote, my county supervisor voted against it. She argued that during rolling blackouts, natural gas helps residents survive without electricity. She's wrong. Without power, most gas appliances won't work. You might get hot water, but my gas stove still needs an outlet. Plus, most hot water heaters hold at least 60 gallons. With rationing, that hot water can go a long way when the power's not on. And in the summer, when these rolling blackouts happen, it's the air conditioning that people miss most. The gas line won't fix it.

So what's holding us back? Why won't we plug the gas lines? My own experience will tell us something about that.

My new house will still have four gas appliances: the clothes dryer (for now), an indoor fireplace, an outdoor fire pit, and an outdoor grill. I've already described what's going on with the dryer. The rest are remaining with the house simply because they're already there, and without the gas versions, I would use wood-burning alternatives.

From what I've read, natural gas is better for public and environmental health. I figured it would be more hypocritical for me to replace a gas appliance with a wood-burning one rather than just keeping the gas appliance we already have.

I don't feel great about continuing to burn gas, but I feel better about this approach than loading up my fireplace or fire pit whenever we want the benefit of fire.

I'd be fine without gas, but since we already have it... why not?

This is going to be the same question everyone will ask when confronted with the reality that sacrifices need to be made by existing homeowners. Their answer may be similar to mine... at least while utilities continue to feed our homes with natural gas.

More from Technology

- Data transformation >> data extraction - Fri 26 May 2023

- Hacking for climate sales - Sun 05 June 2022

- My foray into web3 - Sun 16 January 2022