SOCIALS

From good to great

In: Business

Tags: #entrepreneurship #SaaS #business growth #parallel entrepreneurship

An excerpt from The Parallel Entrepreneur

If you can get your business up to $10,000 in monthly recurring revenue (MRR), then that’s really good. Most entrepreneurs never get there.

It’s good but not great.

Josh Siegel gave me advice that I’ll never forget. I use this bit of wisdom to fire up my drive. He says, “Any $10,000 per month business can be a $100,000 per month business.” These are crumbs, he says, compared to what the larger companies are earning. The hard growth steps, he argues, happen beyond that first $100,000 per month. Less than that is just discipline and some creativity.

He also argues that if your monthly churn is 3% and your net monthly growth is 4% then you will have a phenomenal business. This Rule of 34 (I’ll name this rule on his behalf) is what we should all strive for. You may only get there once in your entrepreneurial career, so to increase the likelihood of doing this, you have multiple businesses running at once.

Finally, a great business has what’s known as “net negative churn.” This is the holy grail of SaaS businesses, when revenue growth from your retained customer base consistently offsets the revenue lost from cancellations.

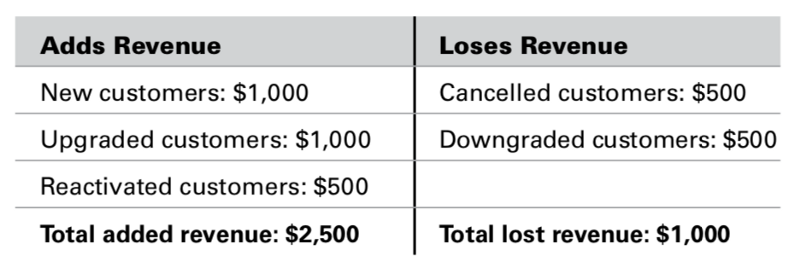

To make this point clearer, let’s look at this table.

Let’s say you’re adding $1,000 of new customers every month. You’re also getting another $1,000 from upgrades and $500 reactivations (customers who canceled and then came back). That’s bringing $2,500 of new monthly revenue into your business.

On the flipside, let’s say you’re losing $500 from cancellations and downgrades each month. This means on net you’re adding $1,500 of revenue to your business each month.

Net negative churn is when, setting new customer revenue aside, you’re still adding revenue every month. In this case, you would be making $1,500 from upgrades and reactivations and losing $1,000 from cancellations and downgrades. You’re adding $500 each month from existing customers.

If you’re able to grow a business before you’ve added a single new customer then you’re in great shape. You can stop reading now, shut your other businesses down, and focus on that one.

I haven’t experienced this yet myself, but I’m working on it. It’s why I still have multiple businesses running today.

Exploiting Synergies

Nobody can run a pizza parlor, a nail salon, and a grocery store at the same time. Even the most ambitious local businessperson couldn’t do that.

But can you open more than one restaurant? Sure, it happens all the time. I think of Tyler Florence and his restaurants El Paseo in Mill Valley and Wayfare Tavern in San Francisco. Same chef, two different restaurants within a few miles of each other.

Can you open multiple cafes? Absolutely. Look no further than the dominance of Philz Coffee, which began in San Francisco’s Mission District and spread throughout the city and then to every corner of the San Francisco Bay Area. (By the way, here’s a fun fact: Phil Jaber spent seven years perfecting his first blend, Tesora, which means “treasure” in Italian.)

I was delighted when a Philz popped up within walking distance of my house in the suburbs 20 miles outside of the city. It’s a perfect example of parallel entrepreneurship applied to brick and mortar businesses.

So what’s the difference between running a chain of cafes and running a slough of disparate shops?

It’s this word: synergy.

Synergy is one of those cliche business terms that gets mocked because it shows up on corporate HR posters and is said around the table in boardrooms. I think it gets an unfair rap. Synergy is a critical concept to embrace if you’re going to be a successful parallel entrepreneur.

As Andrej Danko, VP of product at an artificial intelligence studio that builds and runs multiple companies at once told me, “Doing completely mutually exclusive businesses is very hard. There are no economies of scale. You can’t leverage IP or operational skills across businesses.”

Case Study: Philz Coffee

When you have a busy cafe, some name recognition, and a cult following like the founder of Philz Coffee did, opening the second cafe is a lot easier than opening the first one. Let’s take a high-level look at what’s required to open a new Philz cafe:

Financial needs

- Point of sale terminal- Cash transfers and security- Accountant and bookkeeping

Product needs

- Coffee supply and storage- Coffee brewing devices- Milk, sugar, honey, and other condiments- Baked goods supply

Personnel needs

- Management- Staff- Hiring and training resources

Marketing needs

- Grand opening- Ongoing local outreach

Facility

- Renovation- Lease

Looking at the above list, there are both direct and indirect synergies with the existing cafes. The direct synergies are financial. Phil can use the same point of sale and accounting team. If the second cafe is in the same city then he can also use the same bank for cash deposits.

Product needs are the same. Since Phliz doesn’t bake its own muffins, he’ll need a new supplier unless they’ll distribute out of the city. Same with the coffee roasting. Philz wants only the best, freshest coffee beans (they grind their proprietary blends on the spot) so some supply chain logistics may also be required for coffee beans if the second cafe is too far away.

Indirect synergies are personnel, marketing, and facility needs. Although they won’t be exactly the same (they’ll need a new location, obviously, and new people) the playbook is the same. If it’s not written down then it can be transferred by Phil or one of his first employees at the Mission District cafe.

Let’s imagine, for a second, that Phil decided instead to open a pizza parlor. What synergies would he have then?

Very few.

It would be incredibly difficult if not impossible to launch and run a pizza parlor while simultaneously running a cafe. That kind of parallel entrepreneurship is destined to fail.

When you have a profitable and growing SaaS business, it’s like having one cafe. The nice thing about cafes is they can get more revenue simply by replicating themselves in another location. But you can’t do that on the web. You can’t clone a SaaS business in another location (by giving it a new domain name) and expect to double your revenue. That’s just not how the internet works.

The internet equivalent to opening that second cafe is to start another SaaS business that is separate from the first profitable one but still benefits from synergies.

Case Study: Sheel Mohnot

Sheel Mohnot is another parallel entrepreneur par excellence. After selling his online payments business to Groupon, he started Thistle, a food company that delivers sustainable plant-based meals to homes in major cities throughout California. He also runs a podcast, an auction platform, and a financial technology fund within 500 Startups, a prestigious startup incubator with offices around the world.

He does this all in parallel because he’s found ways to exploit synergies across his projects, delegate his way out of daily management, and turn his cost centers into profit centers.

Let’s dive into Thistle to really see what I mean.

Thistle competes in a very difficult market. Blue Apron, the market leader, went public in June 2017 and its stock price has had a precipitous 70% decline since the public offering. Another major competitor, Plated, sold to Albertsons for $200 million. Other meal delivery services including Sprig, which raised $59 million and was valued at over $150 million, had to shut down.

So what did Sheel do differently? How has Thistle thrived while his well-heeled competitors failed or exited? He successfully approached the problem like a parallel entrepreneur.

First of all, he only raised $1 million for Thistle. He forced his business to run lean, operating profitably from the beginning. Even if you’re small, you won’t be forced to shut down while you’re minting money.

This profitability constraint in turn forced Sheel to be creative. Meal delivery is a complex business, and arguably the hardest part is packaging and delivering meals on time. This cost is often higher than the cost of the food itself. To keep costs down, Sheel found a commercial kitchen that someone else was paying $20,000 per month to use. He negotiated a deal to sublease the kitchen from 9pm to 5am for just $5,000 per month.

Startups that raise gobs of money usually don’t make smart decisions like this. Thistle now serves tens of thousands of customers each week and is profitable with 220 employees.

For Sheel personally, he is a co-founder of Thistle but is not the CEO. That gives him the flexibility to run his auction business, a fund in 500 Startups, and other personal investments that generate meaningful monthly revenue streams.

Read more on Amazon! Buy The Parallel Entrepreneur*.

More from Business

- My best advice for entrepreneurs - Sun 27 April 2025

- Thoughts on building a brand - Wed 25 December 2024

- The process - Sun 29 September 2024